Spend a little time at the Island School with co-founder Chris Maxey and you’ll quickly understand his passion for working with young people to make the world a better place.

“All we’re doing is saying, look, here’s a 16 year old kid, they’re ready to kick ass,” Maxey told us in a recent conversation. “School is BS; the fact that they’re sitting in a building in a classroom, just consuming information, as opposed to getting out there and producing value-added opportunities for the community around them. That’s our driving mission and it’s been the core of our success.”

Maxey and his wife, Pam, founded the Island School in South Eleuthera, Bahamas in 1998. The couple’s initial goal for the program was to “conserve the wild population of marine life [there] by providing alternative food sources and jobs for the people.” In March of 1999, the first, albeit small, group of students and faculty from the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey passed through the schoolhouse doors.

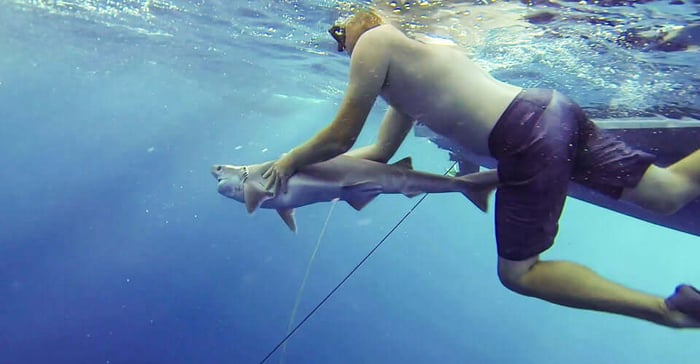

These days, the school offers a variety of courses to around 150 students a year from all over the world. The campus has also grown to include the Cape Eleuthera Institute and the Center for Sustainable Development. Coupled with the incredible natural surroundings, those research facilities allow Maxey and his team to emphasize an immersive learning methodology. Over the course of a normal semester, physical education most likely involves daily training for a four mile, open water swim. Applied science finds students building sustainable aquaculture systems. Humanities teaches the history and customs of the local community through outreach programs, such as working with younger Bahamian students at the Deep Creek Middle School. Marine ecology is studied while scuba diving in the beautiful waters that surround Eleuthera. The hands-on curriculum is ultimately designed to teach all participants how to develop sustainable solutions to real world problems.

“Sustainability is a word like infinity, right? We strive to live as well as we can,” Maxey says. “And we always have monumental tasks in front of us. I would say that our mission is to be as self-sufficient and sustainable as possible. And yet, there are huge opportunities for doing more.”

Maxey rattles off a variety of throughputs the campus addresses on a daily basis. For example, most of the Island School’s food scraps are fed to pigs or composted. Human waste, on the other hand, “is a big challenge.” The school is researching ways to create wetlands that responsibly manage the blackwater. “We also have an ongoing project,” Maxey mentions, “to figure out how to create a bio-digester to turn solid human waste into usable natural gas.”

The Island School does make is its own fuel; Biodiesel created with waste cooking oil from the constant flow of cruise ships that pass through the area. It was a process initiated and implemented by the students. “There were always faculty and engineers involved,” he says, “But they mixed up the first batch, put it in a truck, and drove it around. Now we make 20,000 gallons a year.” Maxey doesn’t like having to depend on the ships, however, and hopes to move towards electric transportation “down the road.”

Those electric cars would be powered by the campus’ intertie system, the first in the country’s history. The network has allowed the Island School to put power back into the local grid for over ten years. About 50% of that electricity is generated with wind and solar. And thanks to an investment from a Canadian utility provider, Maxey says hopes to use 90% renewable energy within the next five years.

Some forms of recycling are still an issue. The campus is able to send off cans and crush glass but there aren’t many options for reusing plastic. “There’s no recycling on the island, so we have to work hard to figure it out,” Maxey sighs. “We’d love to figure out a way to turn plastics back into fuel and not have it go to the dump.”

Recover offers another way to address the plastic problem. We’ve provided the Island School’s uniforms since 2012. The partnership, not surprisingly, was the idea of a student group.

“Two students, as part of their authentic project in human ecology, decided to tackle the uniforms we require our kids to wear” Maxey recalls. “They did some research on the uniforms we were buying. It was non-organic cotton made from a sweatshop in Nicaragua. There was nothing good about the clothing we were requiring our students to buy. We were not wearing our mission at all.

“They put Recover up against Patagonia and Under Armour and some other big brands. Recover won the day for a lot of reasons. You had a full story. There was no, ‘I don’t know where it’s made. I don’t know where the materials come from.’ And it also just felt good. It was lightweight and it held up in our kind of tropical environment where we’re running and swimming and doing all that stuff.”

That anecdote illustrates exactly what Maxey and the Island School is trying to achieve.

“Our students leave here thinking they can really make a difference because we tell them they can and we give them opportunities to. The Recover story is a great example of students problem solving and helping us live better in this place and taking on a leadership role.”

We always jump at any opportunity to visit the Island School. Maxey is a great mentor – one who always pushes Recover to refine our process and our product. Every minor improvement makes a difference.

“Well the reality is,” he says, “It might seem a small thing to find a new uniform for a school or to figure out how to move from styrofoam plates to a dishwasher system at your school. But those little hurdles have huge impact when you think about it. Even little things like turning off the water when you’re brushing your teeth.

I think one person picking up a piece of plastic on the street that might blow into a river that might blow into an ocean, is making a huge difference. And you gotta believe in that.”