BOLIVIA: The New Frontier of Adventure Activism

In less than 30 minutes, a flash flood on the Tuichi swallowed this cobble bar and continued to rise into the jungle banks as the SRSJ Team looked downstream, where they knew the crux whitewater canyon lay ahead.

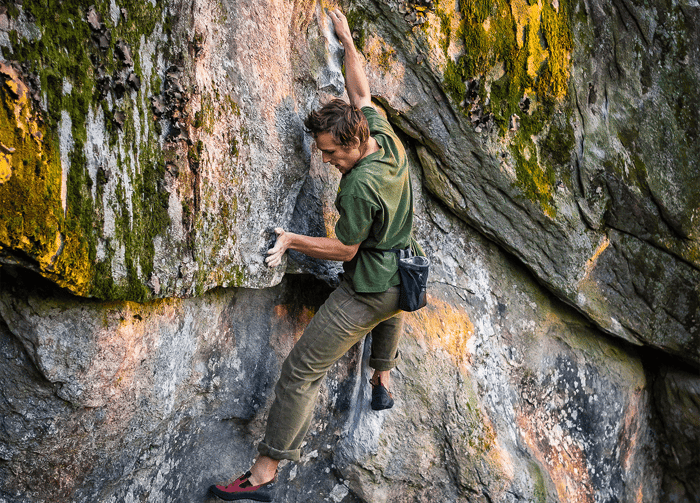

Standing on the cobbled edge of the Amazon’s Tuichi river brushing her teeth, Hayley Stuart had to keep taking little steps back. Despite her steady retreat, in moments, the river was splashing at her feet again. Suddenly rising a couple of vertical inches every minute, a flash flood from heavy rains upstream was swallowing the river banks and crawling into the jungle, just as Stuart and her team were about to leave their night 3 camp and enter the crux whitewater canyon of Still River Silent Jungle (SRSJ), a Recover partner documentary film expedition.

As rocks in the river disappeared in new depths, Stuart and the other kayakers rushed up into the machete-carved jungle camp to pack gear into kayaks. It took them a moment to notice the Bolivian team members adding wood to the fire and settling in. As it turned out, the team was not going anywhere that day… except for deeper into the Madidi jungle to avoid the rising swallows of the Tuichi.

The Tuichi river is the main artery of Bolivia’s Madidi National Park, a majesty of everything from 20,000 ft snow-capped Andes peaks to thick Amazonian jungle. Madidi was recently named by the New York Times as perhaps the most diverse protected area in the entire world. Jaguars, tapirs, river otters, orchids, butterflies, and 8,520 more known species hide amongst each other on the Tuichi (note that Madidi is a relatively unstudied park, and that scientists estimate it is home to at least 11,395 species).

Huddled around the fire under propped tarps in the sporadically pouring rain, the SRSJ team took turns rhythmically waving personal wet river gear just above the flames. Their roots span continents, languages, and expertise. Made up of 4 international whitewater kayakers, the Director of Madidi National Park and 2 park guards, an indigenous river activist, international adventure ecotourism specialists, and representatives from the local mining Asariamas communities and a La Paz ecotourism company, every single person shared a sense of humility and respect for the power of the river, the jungle, and the unique experiences and knowledges held by each other.

The SRSJ Team enjoys a round of individual introductions upon meeting for the first time in a small village en route to the put in of the Tuichi.

Hayley Stuart, the director and producer of the Still River Silent Jungle documentary film expedition is the “smiles against all adversity” figure who brought this diverse adventure activist team together. For Stuart, it all started as a personal interest after a study abroad semester with SIT in Bolivia, where in one class session, she learned about the nationwide plan for large-scale proposed hydropower projects. Upon learning more from diverse stakeholders about the potential repercussions of the projects, Hayley kept in touch with her Bolivian professors and mentors from the program to keep up to date with the progress of Bolivian hydro-development and its impacts.

It was last spring that she found out about the Chepete Bala dam proposal, which, if carried out, will displace over 5,000 people, flood significant acreage of the biodiverse treasure of Madidi National Park including a portion of the park that is known to be the home of still uncontacted Amazonian tribes, and affect the local ecotourism industry that generates more than $15 million to the local economy every year.

It was then that Hayley decided she didn’t have a choice- she had to share at least part of the story with a larger audience, so she immediately began putting together a team of filmmakers, photographers, writers, and partner companies including Recover. The purpose was to give voice to the local communities, biodiversity, and challenges within Bolivia’s Madidi National Park and Pilon Lajas Cultural Reserve through an international whitewater kayak expedition. What could have just been a whitewater kayaking trip, became a means of working with Madidi National Park and the local communities of the Tuichi to explore and illustrate the potential of ecotourism. The team further realized the profound impacts of adventure whitewater training for conservation.

“From the beginning, it was a constant debate of what this trip was going to look like,” Stuart recounts. “Originally, we just thought we would be doing a self-support kayak trip, and then all of a sudden Kalob Grady and I are trying to check kayaks, film equipment, 2 rafts, and a bunch of raft equipment at the airport in Portland so we can take park guards and local community members down the river with us, and train and donate a raft to Madidi National Park. In planning, we had to coordinate with local communities and the national park to even enter the park, and we found out that if we didn't have a raft to take people down, we wouldn't be allowed on the river. Then, the airlines shut down the rafts, I flew to LA, got delayed and figured out I could take the floor out of one of the rafts and check it as two pieces so that the airline would take it, flew back to Portland, got it on the plane, and then our key logistics coordinator in Bolivia, Sergio Ballivian found another raft for us to borrow in La Paz upon the condition that someone from the raft company could come and attempt the river in a kayapo, which is essentially an on-the-spot, hand-built raft from cut down trees and inner tubes.”

When the only beta you have is that somewhere downstream is Class V, it goes without saying this could be worrisome. But the international team is soon humbled by the extraordinary on-the-water river skills of the locals.

Needless to say in the tumultuous obstacles, surprises, and negotiations, there was hesitation and discussion about how to provide river safety in the best way with so many unknowns. The kayaking team members were ready to man the rafts if necessary, but all hesitations quickly floated away once the diverse team united at the end of a winding dirt road that plummeted from high mountains into the jungle and landed at an open calm-moving section of the Tuichi.

Kalob Grady stretches his legs on the drive past the 21,000 + foot peaks of the Royal Mountain Range.

“Once we all got together, there was this incredible synergy between so many different people and so many different perspectives,” described Stuart. “One of the purposes of the trip was to promote adventure ecotourism in the region as an alternative to the illegal gold mining in the National Park that is currently being developed, largely by the Chinese. The new mining uses a lot of industrial machines and unregulated mercury, but the area has so much potential to further develop adventure ecotourism that would benefit locals and promote conservation of clean water and the rich biodiversity of the region. By actually working with local communities on our trip, the community members got to see an alternative means of ‘development’ that demands the region be intact, instead of resulting in intense social and environmental repercussions. There was this eye opening of how ecotourism could benefit them, and really, they are such experts. They know so much about jungle, the river, the legends and the plants and how to track animals. We quickly realized that just because we might be international kayakers, the Bolivian team members were the real river people because they were part of it, they grew up on it, and their families and tribes had been there for centuries and millennia.”

Another realization of the international portion of the team was the immense impact of training the National Park guards in how to maneuver a raft through challenging whitewater. Lorenzo Andrade-Astorga, the captain of the Chilean National Rafting Team, headed the training. During his days on the raft, he learned that for the Madidi park guards to patrol this section of river by foot for illegal mining, logging, and poaching, it took at least 21 days, while on a raft, they could do the same work in 5.

Lorenzo Andrade-Astorga, captain of the Chilean National Rafting Team, professional whitewater kayaker, and filmmaker, producer, and co-owner of Nomade Media leads an introduction to rafting at the put in of the Tuichi with Madidi National Park guards and community members of the local territory.

Reflecting, Hayley describes, “Whitewater adventure training and tourism can have real, significant positive impact. What may get lost in kayaking the world is that sometimes we don’t interact with locals. We come, stay in our group, and simply take our individual experience home with us. This trip was extremely special because to be able to be with the people who called the Tuichi home every day, and to see the land not just from whitewater eyes, but from their eyes of living there and being a part of jungle, was really enlightening. We always get so much, and this trip felt like we received more than ever because we got to share and give back a little bit. It’s certainly not over! We are still fundraising, and working to tell this story through the locals’ own voices. Still River Silent Jungle will be complete this December for international distribution, and we are working with Madidi National Park to continue a partnership both for further whitewater training of their park guards and with the local communities for distribution of the film throughout Bolivia. We’re lucky because Recover was simply a perfect partner for the film because of the company’s conservation values and that mentality of being part of a solution rather than a problem.”

The next morning, the Tuichi river was still swollen and lapping against its newly claimed territory, but it had dropped ever so slightly from its flash flood peak. Without a word, the SRSJ team packed up, put on, and entered the canyon.

Follow more of the SRSJ expedition with Recover this week on our social, and share your own inspiration with Recover in the Wild, from the backyard to beyond.